Art is generally accepted as a “free” form of creative expression — one that allows its creator to explore various visual outlets through the artist’s own will and for the artist’s own personal fulfillment (1). While this is an accurate description of the spirit of art, it is not a necessarily honest reflection of the objectives, or motivations, behind even some of the greatest masterpieces of the art world.

In many cases, honoured historic art clearly served an applied function at the time of their creation – these celebrated works in the history of World Art were produced out of a third-party contract, or had a definite purpose, be it in the name of the Church, for a wealthy patron family, or to portray a significant event or individual in a particular light (1). For example, Leonardo da Vinci’s La Gionconda, better known as the Mona Lisa, was a commission for the portrait of Lisa Gherardini, a cloth merchant’s wife (2). A commission is motivated by a third-party, and thus, it cannot be agreed that Leonardo was completing this piece out of his own free will, as ‘art’ supposedly requires, compensatory benefits aside. What would be left for us to hang in our galleries, if even the Mona Lisa fails to qualify?

Both commercial art and fine art has been traditionally created, and sold, for money. While graphic designers today seek the business of companies and professionals, the visual communicators in history were most often artists who sought patronage and commissions from power figures. One of the most obvious examples of this is the influence of the Medici family upon the arts in Renaissance Italy.

From their emergence in the 13th century to their decline in the 17th century, the Medici family supported the famous careers of individuals such as Galileo, Michelangelo, Massacio, and Leonardo da Vinci, who also prospered under the patronage of the Duke of Milan and King Francis I during his lifetime. The Medici’s wealth and deep appreciation for beauty not only drove Florence to the forefront of cultural development, but also allowed for them to maintain a dynastic image of themselves directly through their portrayal in commissions.

“The Medici surrounded themselves with visual images denoting rulership, although they steadfastly maintained that they were ordinary citizens within the republic. The differences between appearance and reality could not help but affect the art produced within the city”.

Paoletti, John T. , Radke, Gary M. Art in Renaissance Italy. Prentice Hall, 2002.

Though the idealistic conception of ‘art-for-art’s-sake’ is not so easily applied to many works, it does not mean that the value of their integrity as art is at all diminished. The personal investment and talent of each artist is clearly expressed on every canvas. The direct patron-artist transaction experienced a significant shift as sociological status structures were shaken around the time of the French Revolution at the end of the 18th-century, during what is marked as the “end of absolutism” (1). The alliance between traditional patrons and artists gradually dissolved as the power of these figures diminished in society.

It is at this time that the concept of the carefree “bohemian” artist shifts from being a 300 year-old idea into actual practice. As a result of this, the idea of art as being a boundless, uninhibited creative practice also takes shape beyond the confines of what was up until 1800 considered a more applied approach. This new era of ‘freedom’, however, was nonetheless affected by powers in society, re-appearing as representatives of the Industrial Age (1). Since the Golden Age in Greece, the artist was also the artisan, crafting pieces that were artistic yet also functional. Famous masters of art are known to have been practicing scientists, architects, and even military engineers.

“Each has within him the undying desire to create, to contribute something to the world, to leave his mark upon society; each has the necessity to earn and provide a living for himself and his family”.

Walter P. Paepcke

The American Industrialist Walter P. Paepcke (1946) observed that this correlative practice was nullified with the onset of the Industrial Revolution in the 19th century, as industrial specialization skills created a deviation away from artistic philosophies.

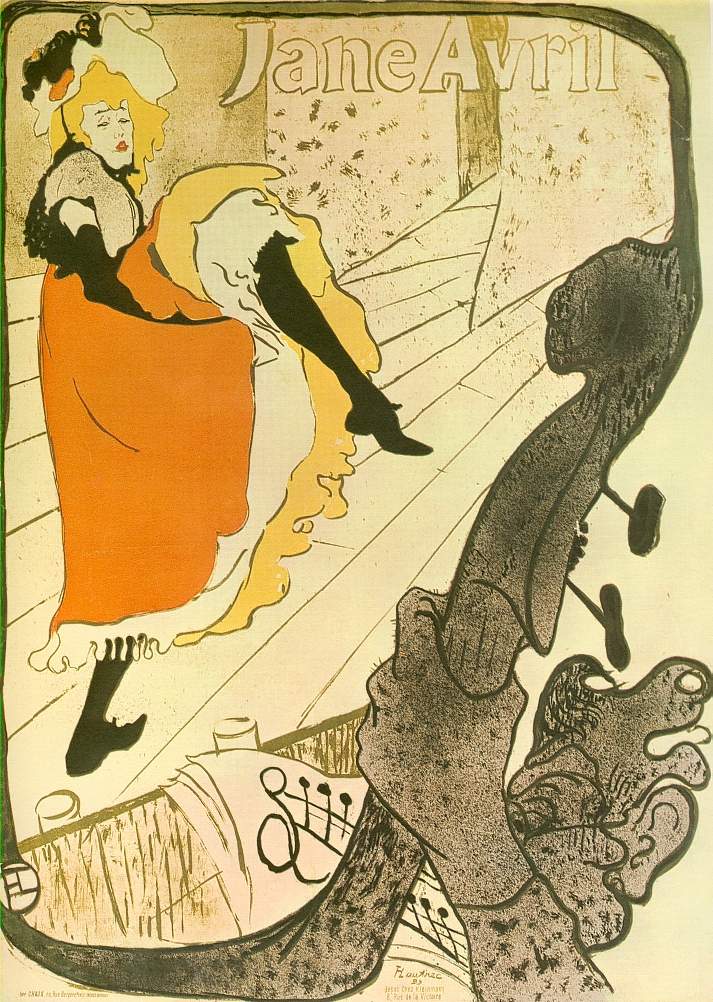

However, a growing number of artists began using the drastic social changes to their advantage, and re-aligned art with application once again. Ironically, one such artist is the very symbol of the Bohemian artistic movement: Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, whose flamboyant artistic character co-existed and contributed to the success and functionality of his trademark posters. While the Industrial Revolution was seducing artists with the prospect of commercial work, political revolutions around the world were luring artists into graphic design.

In defence of the integrity of art, we might ask, “Does that make their works less valid as art? Is art not really art if it’s produced for money?”. A reflection upon the the fine art industry of yesterday and today would affirm that the amount of respectable art flowing through our galleries would be meagre indeed if our artist’s lacked the desire to succeed (be it financial success or fame).

(1) Rotzler, Willy. Art and Graphics, Reciprocal Relations between Contemporary Art and Graphics. Ed. Jacques N. Garamond. Zurich: ABC Edition, 1983.

(2) “Portrait of Lisa Gherardini, wife of Francesco del Giocondo.” Louvre. 2006.